JOHN CHARD UNDER FIRE!

A Wild Night at 'Fort Funk'

A night-time panic in a British camp; possibly the same incident at Fort Newdigate which almost cost the life of John Chard, the hero of Rorke’s Drift.

On the night of 6 June 1879, a particularly severe false alarm took place in the British camp at Fort Newdigate – and very nearly cut short the career of arguably the most famous hero to emerge from the Anglo-Zulu War.

In the aftermath of iSandlwana, false alarms became common-place among British columns operating in Zululand. Whereas British troops had begun the war with a relaxed confidence, convinced that the Zulus lacked the courage and discipline to withstand concentrated British firepower, the devastating losses at iSandlwana on 22nd January had led them to come close to fearing them instead. While those battalions who had been serving in southern Africa since before the war were generally experienced enough not to be unsettled by exaggerated tales of African bogeymen, and by the strange sounds of the African night, those hurried out quickly as reinforcements from the UK were more susceptible. Many battalions had hurriedly been made up to active strength by the incorporation of drafts of young soldiers who had only just completed their training, and who had not yet gained the confidence that comes with experience in the field. Most of the reinforcements sent out, furthermore, had heard tales of Zulu ferocity and ubiquity while still a long way from the front. Lieutenant Arthur Mynors of the 3/60th had first heard stories of the carnage at iSandlwana from Rupert Lonsdale when the battalion stopped to refuel at Cape Town; by the time the 60th had reached the Thukela river, destined to take part in the Eshowe relief expedition, Mynors had formed the opinion that

No one knows where the Zulu armies are; one day they are seen at one place, another at another; one meal lasts them for three days; and the bush they can creep through like snakes. Being nothing but Zulus…about the country here, they come and watch us; in fact they know everything that goes on. They are awfully wily; they are never to be caught in open country …the only time they will attack their enemy is before daybreak, and at night when we encamp … (1).

Stories like this, spiced with added lurid (and in fact fictional) details of the ‘little drummer boys’ killed and mutilated at iSandlwana, circulated widely, and each new Zulu victory seemed to add credibility to them. Small wonder that soldiers fresh out from England, some of them serving overseas for the first time in their lives, found their nerves stretched to breaking point as they took their turn on picquet or sentry duty, marching outside the safety of the camp lines, in the oppressive strangeness of the African night. It was easy enough to interpret something moving, half-glimpsed on the very edge of a field of vision, as an impi stealthily approaching – a challenge unanswered, a shot from a picquet, and quickly the situation could escalate beyond control. During the siege of Eshowe one false alarm was provoked one night at the sight of something white slowly moving to and fro; it turned out to be a sailor’s shirt, washed in a nearby stream, hung out to dry and forgotten, and flapping gently as a breeze came on. Early on the morning of 6th April, during the withdrawal from Eshowe, another more serious incident took place when a picquet of Mynors’ regiment, the 3/60th. Mistook figures moving in the darkness for Zulus and opened fire; in fact they were a forward screen of the followers of the ‘white Zulu chief’, John Dunn – their own men – and before a halt could be called two were killed and several more wounded.

The most serious incident, however, very nearly cost the life of John Chard, the hero of Rorke’s Drift.

After weeks of preparation, Lord Chelmsford had begun a fresh offensive – a second invasion of Zululand – on 1st June. His main thrust was a column composed of reinforcements out from the UK, and designated the 2nd Division. The 2nd Division had assembled at Landman’s Drift on the Ncome river, then moved forward to Thelezeni hill, and finally begun its advance, striking south-east in a direction which would by-pass the old iSandlwana battlefield, and join the old January planned line of advance near Babanango mountain. At the same time, Col. Evelyn Wood’s column – the old Left Flank Column, now designated the Flying Column – was to move south and affect a junction with the 2nd Division. The two would retain separate command and administrative structures but would advance in tandem, a few miles apart, so as not to foul too large an area with a combined camp; if threatened, however, they were close enough together to combine and fight as one.

The two columns had achieved their junction on 2 June, but the first week of the invasion had not proved easy. On the day it began – the 1st – the Prince Imperial of France had been killed in a skirmish whilst patrolling ahead of the 2nd Division, and on the 5th a skirmish between the Division’s mounted troops and Zulus at the foot of the eZungeni hill had resulted in the death of the 17th’s adjutant, Lt. Frith. Both incidents had undoubtedly heightened tension within the 2nd Division, particularly among those regiments fresh out from the UK who were experiencing something of the truth behind the Zulus’ fearful reputation for the first time.

On 6th June the 2nd Division built a fortified post named Fort Newdigate – after Major-General Edward Newdigate, the commander of the 2nd Division – on an open rise above the Nondweni river. The actual fortifications were small – a square entrenchment, with rough stones walls on the inside, and a rather weaker construction about forty yards away. These two redoubts, which were big enough only to comfortably contain a company of men, were intended to stand as bastions at either end of a square or diagonal wagon laager in between, formed of the column’s transport wagons. The tents of the accompanying troops were pitched outside the laager but in the event of an attack the men were directed to strike the tents and rush within the protection of the wagons which were sufficient to provide a practical defensive position, in contrast to the unprotected camps of iSandlwana days. Having reached this spot, it was decided to stockpile supplies at Fort Newdigate for the next stage of the invasion. The Flying Column, which was advancing a few miles ahead of the 2nd Division, was ordered to halt in order to be able to provide an escort for a train of unloaded wagons which was then due to march back down to collect fresh supplies. Since the 2nd Division included only 55 Royal Engineers a detachment of men from Captain Walter Jones’ 5th Field Company RE, attached to the Flying Column, were sent back to Fort Newdigate to assist the 2nd Division in constructing the forts and laager. They arrived late in the afternoon of the 6th, and camped close to one of the forts.

The atmosphere within the camp at that point seems to have been tense. Many of the troops were young and untested, and during the time they had been on hostile territory they had experienced the death of the Prince Imperial and the skirmish at eZungeni. Further more, on the 5th, a number of Zulu envoys, sent by King Cetshwayo to ask what terms the British would accept for peace, had been entertained at Fort Newdigate before being sent back with an answer. There seems to have been a feeling that events were gathering pace, and that something was about to happen..

Late in the evening, in readiness for the night, picquets were placed outside the laager - a screen of men from the 58th Regiment and beyond them a line of auxiliaries. Those men not on duty settled down in the tents outside the laager, although with the centre crammed with pack animals it was hardly a quite. What happened at about 9 PM is graphically described by Captain W.E, Montague of the 94th Regiment;

I was lying snugly in my bed – two blankets and a waterproof sheet laid out on some charming specimens of quartz – having further indulged in taking off my boots, in anticipation of a good night’s rest, when ping! ping! ping! went three shots, the signal of an attack.

In an instant the drowsy camp awoke as if by magic. The Native Contingent crowded into the laager, buzzing like bees. Our own men raced each other, in an effort to be first within welcome cover. The bugles rang out the ‘assembly’, a weird sound; between the pause were heard the words of command. Flop came the tent around my ears, and I was outside in the darkness. The air was full of noise and hurry and bustle. Confusion put in its own voice, and was heard. From a rift in the clouds a streak of light fell on the heads of silent men in the wagons peering out, and gave promise of the rising moon. Here and there flashed a bayonet, pointing outwards. Inside the wagons was a space, ten yards across, left vacant for a roadway, and within this lay the vast crowd of oxen, tied by the head, and breathing noisily. Between them, here and there, were the horses, picketed in lines, straining nervously at their head ropes; the men beside their horses, in readiness to mount.

At that moment came a volley far down the hill where a picket had been posted, its rattle clear and distinct in the night air. A staff officer gallops past; and in an instant the rear face is lit up with fire, taken up all along the line of wagons. Crash go the volleys everywhere, belching out flame and smoke, till the front is one thick white cloud, pierced only by the sharp and vivid flashes of the muzzles. ‘Whish!’ comes a bullet overhead. ‘Whir!’ follows another after. Crash goes a volley close by, and the face in front is once more framed with fire. Then the big guns in the corner give out an answer, booming their base notes high above the rest. The bullets are flying merrily overhead; and the soldiers, young lads half of them, with a wholesome dread of the Zulus in their poor little hearts, and funk written plainly on their faces, crowd under the wagons for safety, quickly to be pulled out again by their officers in every state of undress, many with their red nightcaps still on Out come the skulkers in droves, only to vanish again around the next wagon. The fun grows furious. Bullets sing and whiz past in flights. The smoke is stifling, and hides up everything. Half-a-dozen horses, maddened by the din, are rushing about. In the narrow pathway left around the wagons it is impossible to move freely, so crowded is it with oxen and horses. Native soldiers squat in masses in the middle, and continually let off their guns in the air, keeping the butts firmly on the ground. Conductors blaze away into the nearest wagon-tilt. Tents lie flat, their ropes still tied to the pegs, sure traps for the unwary. Chaos is everywhere, even in the wagons, where the men lie, firing incessantly, and paying but scant attention to the orders shouted at them. (2).

It was worse, however, for those whom the alarm caught outside the lager – including the newly-arrived part of 5 Field Company RE, among whom was none other than Major John Chard, the hero of Rorke’s Drift. A recently discovered account gives a vivid impression of the Engineers’ experience, and just how close Chard came to getting shot by his own men. ‘Between nine and ten I was awakened by a rifle shot’, wrote one of them in a letter home to his family,

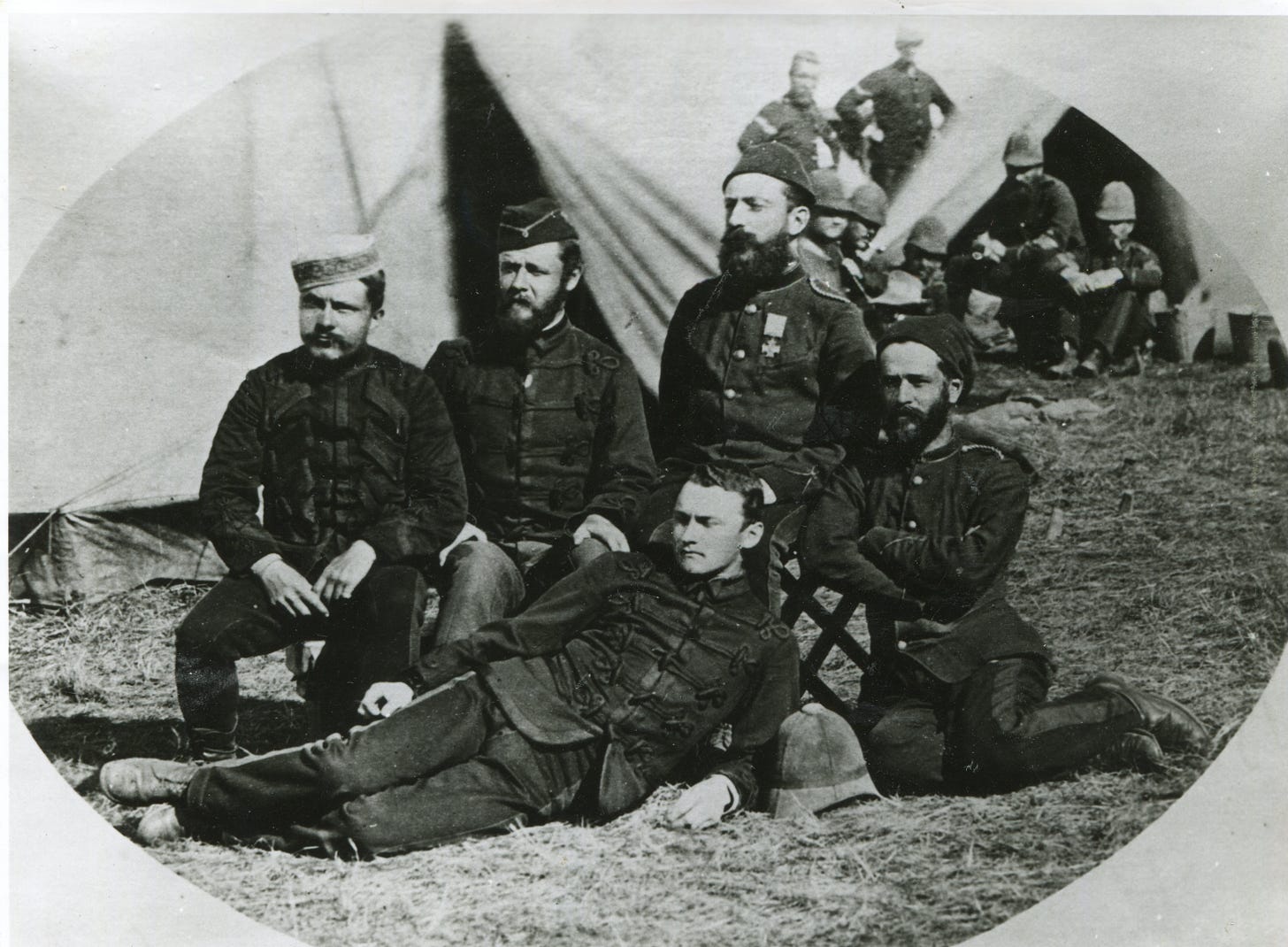

John Chard (wearing his VC) and fellow officers of the Royal Engineers at the end of the Zulu campaign.

I sprang to my feet, grasped my rifle, and made for the door [of the tent]. Just then another shot was fired, and another. I doubled off to the laager, and took up my position. Just as we had got in the outlying picquet fired three volleys, and then began to retire on the big laager, but we called them into ours. We were all stood up at our posts, when bang came a volley from [the] laager right into us. ‘Good heavens, they are taking us for the enemy, under cover at once!’ cried Chard (the hero of Rorke’s Drift). The wall was only two feet high, so the men got under the wall, only inside I and a few more stood our ground – indeed, it was not safe to move. The buglers shouted the ‘cease fire’, and for a moment they ceased. Our men got over the wall to rush on the laager, when they, taking us for a rush of Zulus, poured another volley into us. Back we had to go helter skelter over the wall. Men jumped onto one another, and were lying huddled in hopeless confusion, while shot was pouring into us like hail. The two buglers again sounded the ‘cease fire’. At last it did cease; then we looked round for casualties. We found one sergeant shot through both legs (the thigh), one of our drivers’ hand shattered, and two fingers shot off Corporal Callingar, a piece shot off his chin, Corporal Stewart’s cheek-bone grazed. Driver Miles, a bullet caught his brow and scooped the flesh off;, one horse shot dead on picquet lines, and one shot right through the shoulder. My tent had a bullet through it. I found the bullet next morning in my blankets (I am keeping it in memory). How any of us escaped God alone knows. My chum on my right hand had a bullet strike his rifle. I was near blinded by the earth knocked up by the bullet. Some of the men were hurt by splinters of stone. Next morning we found the stones on the wall covered with lead and bullet marks. The artillery told us they were just going to fire when they heard our bugle sound. If they had opened fire not one of us would have escaped. (3)

According to one unidentified member of Wood’s column the Engineers

…saw the state of affairs, and had the presence of mind to keep as flat as flat on their faces behind the low walls of the fort as possible; but one or two sappers, who attempted to stop the fight, were wounded. (4).

The chaos lasted for about twenty minutes before the troops could be persuaded to stop firing and order restored. The same writer was unimpressed;

… so absurd was the whole affair that some of the men actually fired on their own and their officers’ tents – which were of course struck as soon as the alarm was given – and in many instances riddled the tents, the clothes, the cooking utensils under them with bullet holes, so as to render them completely useless. It is said that several officers’ helmets had holes in them from bullets, but these I did not see. It is quite possible that a helmet left in a tent would have been as badly treated as the tent itself …(5).

Captain William Molyneux, ADC, confirmed ruefully that ‘all the camp kettles, tents and kit left outside one face were perforated … and one regiment did most of its cooking in mess-tins afterwards’. Once order was restored efforts were made to determine what had happened, and according to Molyneux

Some groups of natives were posted with the outlying picquets, and one of these began firing about eight o’clock; whereupon the pickets retired to the unfinished forts, the tents outside the trench and laager were struck, and the men fell into resist an attack…When quiet was restored it was found that the enemy consisted of stray ox or so… (6).

Captain Montague recalled how the affair ended – and the response from General Newdigate;

…the flashes die out and leave the laager dark and silent as the night itself. Then our General followed, and gave his censure pretty freely on the wretched scare; and shame sat on many a face at its recollection. Not a Zulu had been seen – the picket who had commenced the row firing at what it thought was some ‘blacks’ but might have been a cloud… From that day, the spot where it happened was called, in memory of it, ‘Fort Funk’.(7).

The war soon moved on from Fort Newdigate, which soon became no more than a garrisoned supply post on the lines of communication, and the one dramatic night in its history largely forgotten. It is interesting to note that, despite the seriousness of the wounds inflicted they do not seem to appear on official alty returns. The 2nd Division marched on, although the incident did little to calm the nerves of the troops involved, and there would be more scares in the few short weeks before the war ended. As to John Chard, he escaped the injuries inflicted on his men but ‘Fort Funk’ was the second time his life had been at risk in the Zululand night, and he would risk it again a month later, when 5 Field Company were present at the battle of Ulundi, and were deployed to reinforce a section of the British square under a particularly determined Zulu attack.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My Thanks to Lee Stevenson, whose indefatigable research turned up the previously unpublished newspaper account from the anonymous member of 5 Field Company.

NOTES

1). Letters and Diary of the late Arthur C.B. Mynors, private family memoir, Margate, 1879.

2). Campaigning in South Africa; Reminiscences of an Officer in 1879 by Captain W.E. Montague, William Blackwood and Sons, London,1880.

3). Account by an unnamed member of 5 Field Company RE, published in the Gloucester Mercury 2nd August 1879. ‘Corporal Callingar’ is presumably a misprint for 2nd Cop. 9114 George Callingham. ‘Corporal Stewart’ is Corporal 1173 C.E. Stewart, and ‘Driver Miles’ Driver 10738 W. Miles. Sergeant James McDonald’s service papers confirm that he was the NCO wounded in the thighs. All four were in 5 Field Company.

4). Unidentified correspondent with Wood’s (Flying) Column in The Globe, 26th July 1879.

5). Ibid.

6). Campaigning in South Africa and Egypt by Maj. Gen. W.C.F. Molyneux, London, 1896.

7). Campaigning in South Africa, Montague.