Prince Gilenja Biyela

In April 1996 I was lucky enough to sit in on an interview with Prince Gilenja Biyela, a member of the royal family of the Biyela clan, whose heartland lies east of the Melmoth heights in central Zululand, and who was perhaps the only genuine Zulu oral historian I have met. I was staying at the Simunye cultural lodge, nestled in the valley of the iMfule river, and while I was there a UK production company had been filming a documentary about the events of 1879. They had arranged for Prince Gilenja, who lived nearby, to be interviewed, and I was lucky enough to attend.

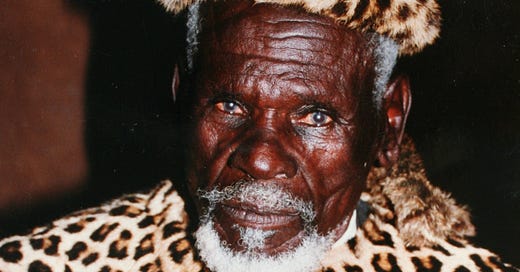

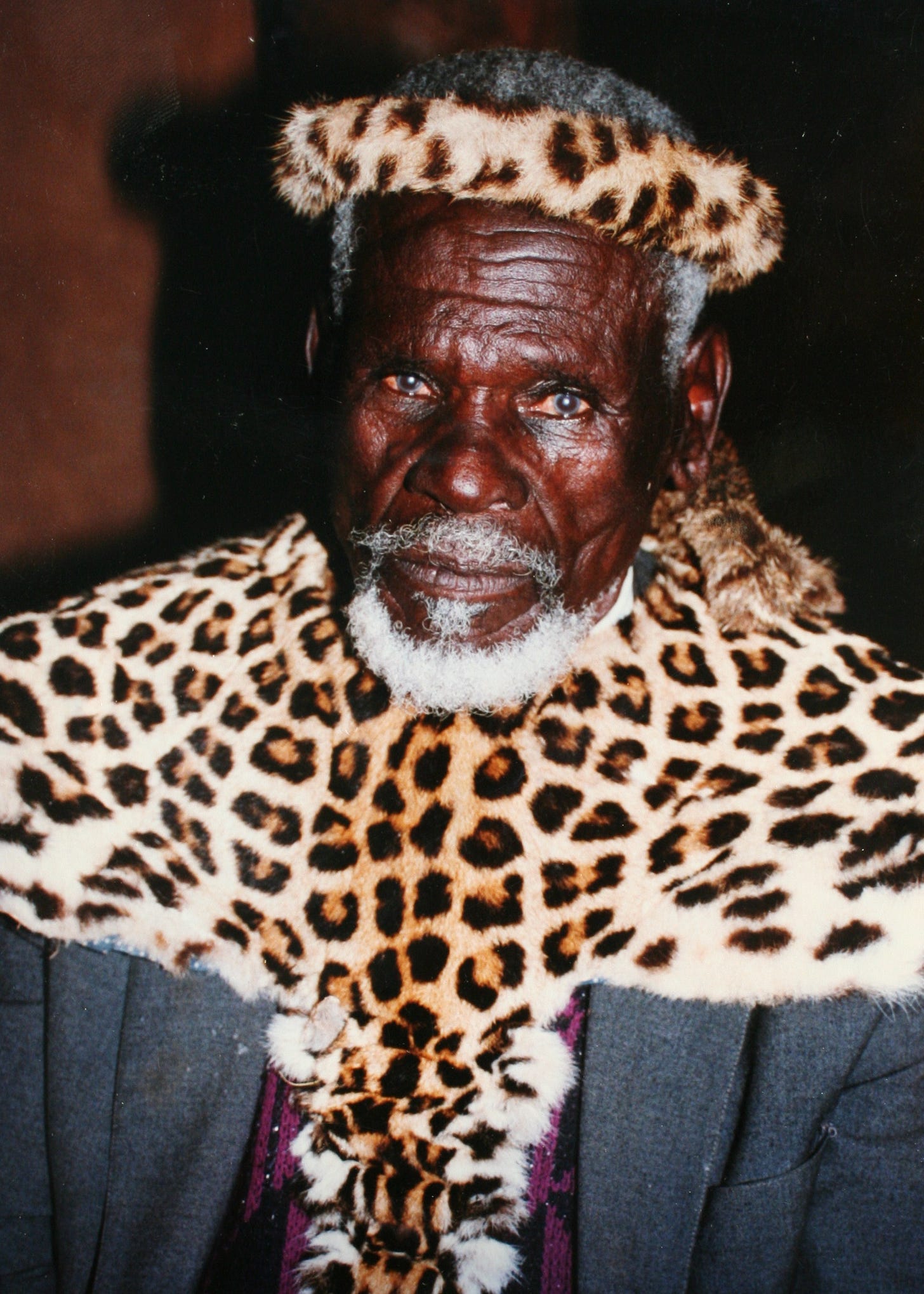

Prince Gilenja proved to be a wiry man with sharp, questioning eyes, who seemed to be in his 80s; he was dressed in European clothes and had a rather crumpled look, but before the cameras started rolling he put on an umqele, the traditional Zulu headband, and the leopardskin collar, umbatha, which is a mark of royal blood, and as he did so something seemed to stiffen and swell in his manner. He knew his interviewer well – the great Zulu cultural expert Barry Leitch – and had been introduced to the crew; I, however, was an interloper, and he looked me up and down, demanding to know my credentials. On being told that I was a historian, he fired a question at me in isiZulu, which Barry translated – ‘He says, if you are a historian, what did Mkhosana Biyela say at iSandlwana?’

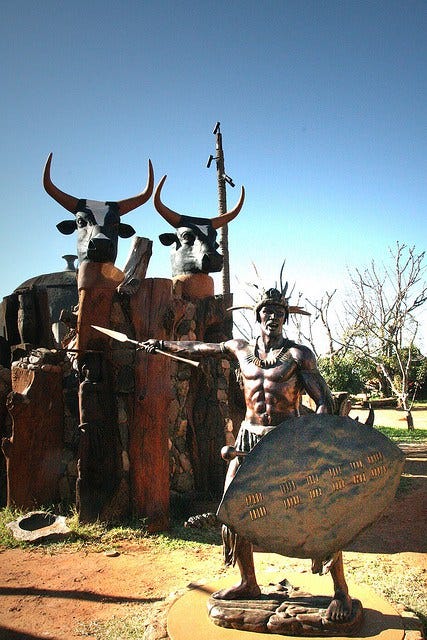

Now fortunately I knew something of Mkhosana kaMvundlana, who was an inkosi (chief) of the Biyela in 1879. The Biyela had allied themselves with the Zulu early in the career of King Shaka, and they enjoyed a high status within the kingdom because they had never been defeated by the Zulu; in 1879 Mkhosana Biyela, who was a man in his forties and enrolled in the iNdlondlo ibutho, held a command in the uKhandempemvu regiment, and he seems to have been on the staff of the Zulu general Ntshingwayo kaMahole during the iSandlwana campaign. At the height of the battle, the uKhandempemvu formed part of the Zulu centre, or ‘chest’, attacking the British camp but they had found their advance bogged down by the rifle-fire of the 24th Regiment in front of them, and had taken shelter in a series of dongas. On the hillside above them, Ntshingwayo had recognised that their predicament was in danger of holding up the whole Zulu advance, and he had turned to Mkhosana, standing nearby, and ordered him to urge the uKhandempemvu on. Mkhosana had scooted down the steep slope of the iNyoni escarpment and had strode up onto the forward lip of the dongas, pacing up and down and haranguing his men. Drawing on a well-known praise-name for King Cetshwayo, he called out that the king had not ordered them to lie down, and, their honour stung, the uKhandempemvu rose up out of their cover and charged. It proved a turning point in the battle and ahead of them the 24th abandoned their extended firing position and retired back towards the tents, and within minutes the battle dissolved into a fierce hand-to-hand melee.

A statue depicting Mkhosana Biyela urging his men on at iSandlwana.

‘He asks’, said Barry, ‘what did Mkhosana say. How did he refer to the King?’

Suddenly very conscious of those rather fierce eyes burning into me, and that I had to say it in isiZulu, I managed to mumble ‘uHlamvana bul’mlilo kashongo njalo!’ – ‘The Little Branch of Leaves That Extinguished The Great Fire gave no such order as this!’ Hau! Prince Gilenja settled back in his chair, satisfied that I wasn’t a complete fraud; but, he said, holding up a stern finger, I had missed a bit – the full quote from the King’s praises was ‘uHlamvana bul’mlilo ubaswe uMantshonga no Ngqelebana kashongo njalo!’ - ‘‘The Little Branch of Leaves That Extinguished The Great Fire kindled by Mansthonga and Ngqelebana gave no such order as this’. The difference was significant for Mantshonga and Ngqelebana were the Zulu names for two white men, Captain Joshua Walmseley – a Natal border agent – and a trader named Ephraim Rathbone. Although the reference to ‘extinguishing the great fire’ might seem obscure now, every Zulu in 1879 would have understood that it commemorated the incident in which King Cetshwayo secured his succession to the throne – the moment when he ‘extinguished the great fire’ formed by the challenge posed by his rival, his brother, Prince Mbuyazi kaMpande.

That dispute had been resolved in one of the bloodiest battles in Zulu history which – as I’m writing this – took place 168 years ago today, on 2 December 1856.

Unlike his predecessors, the Kings Shaka and Dingane, King Mpande had fathered a large number of sons but, as they grew towards manhood in the 1840s, rather than confirm his successor he preferred to keep them all guessing by hinting that he supported first one and then another. By 1853 two principle candidates had emerged, the Princes Cetshwayo and Mbuyazi. and whilst Cetshwayo had the better claim the King seemed to prefer Mbuyazi. Both sides began canvassing support within the country and factions grew up around them - the uSuthu of Prince Cetshwayo and the iziGqoza of Prince Mbuyazi. It seemed that Cetshwayo was more popular within the country, however, and Mpande quietly advised Prince Mbuyazi to flee with his supporters to Natal, and beg the colonial authorities for support - much as he had done when he secured Boer support to become king in 1840. Throughout the middle of 1856 Mbuyazi made his preparations and at the end of November he made a break for the border. His followers numbered about 20,000 people, but only about 7000 of them were fighting men. The iziGqoza reached the river to find that it was full, and largely impassable; a small group of white traders, including Rathbone, who was well-known in Zululand, who had been in Zululand as the crisis broke and had also tried to flee, were trapped alongside them on the Zulu bank, although many had driven their cattle - the profits of their trading - onto a sandbank near the Natal shore in the hope of keeping them safe. Mbuyazi appealed to the Natal authorities for help but Natal did not want to get involved in a purely Zulu affair; the Border Agent at the Lower Drift, a Captain Joshua Walmsley, did allow his young assistant, John Dunn, to cross the river with a number of armed Africans, ostensibly to try to maintain order; in fact Dunn agreed to fight for Mbuyazi.

As soon as he saw his brother's move Prince Cetshwayo gathered his fighting men - over 15000 of them - and set off in pursuit. He arrived at the river on 1 December 1856 and prepared his troops to attack. Prince Mbuyazi, meanwhile, had thrown his warriors out in a screen on a ridge towards the enemy, and had hidden his non-combatants in the undulations between them and the river. John Dunn's musketeers took up a position on Mbuyazi's left flank.

The ‘Ndondakusuka battlefield; Prince Mbuyazi’s forces were drawn up on the ridge on the sky-line, left, but were driven towards the Thukela river in the foreground. The white traders had attempted to secure their cattle on the sandbanks mid-stream.

The battle began early on the 2nd. The uSuthu, with Prince Cetshwayo directing them from behind the centre, attacked in the traditional 'chest and horns' formation. On the iziGqoza left Dunn's men held up the advance of the uSuthu right horn but fate intervened to inspire the collapse of the iziGqoza centre - as he was watching the enemy advance a puff of wind took the tall crane feather Prince Mbuyazi wore in the centre of his headdress and cast it on the ground. It was such a clear and obvious omen to the men around him that the heart went out of them. As the uSuthu approached they fell back off the ridge, and collided with the non-combatants in the valleys behind them. The uSuthu rushed forward and the battle degenerated into a panic-stricken rush for the river with the uSuthu killing iziGqoza warriors and non-combatants alike. Hundreds were driven into the river only to be drowned or taken by crocodiles - their bodies were washed out to sea and littered the coastal beaches for miles. John Dunn himself only just managed to escape - Prince Mbuyazi was killed. At least 15000 iziGqoza were killed, and their bones have continued to turn up in the sugar-cane fields that now cover the site into recent times,

When they reached the river the uSuthu crossed to the sandbanks where the traders' cattle were gathered, politely greeted the traders, and drove away their cattle.

The battle established Prince Cetshwayo as heir apparent, although he did not succeed to the throne until his father died peacefully of old age in 1872. After the battle, John Dunn went to the traders who had lost their cattle and offered to get them back in return for a cut. Despite the fact he had just fought for Prince Mbuyazi, he went to Prince Cetshwayo, explained the situation and asked for the cattle back. Cetshwayo agreed to return them - and was so impressed by Dunn's nerve that he offered him the role of his white adviser. Dunn agreed - and soon after moved to Zululand, embarking on his career as a 'white chief of the Zulus'.

The battle affected Zulu politics for years afterwards. After his victory Prince Cetshwayo worked to shore up his support among his brothers, and to eliminate those whom he suspected of harbouring their own ambitions. Three important members of the Royal House fled Zululand, the Princes Mkhungo, Mthonga and Sikhotha. When conflict with Britain loomed in 1878 these princes allied themselves with the British in the hope that King Cetshwayo would be overthrown and their faction might enjoy a resurgence; several hundred iziGqoza supporters formed part of the 3rd Regiment NNC and fought throughout the iSandlwana campaign. Prince Sikhotha himself fought in the war - he narrowly escaped at iSandlwana. Prince Mthonga allied himself to Col. Wood's Left Flank Column, and was present on Wood's staff at the battle of Hlobane. After the war, however, the British decided to reduce the influence of the Royal House and saw no further use in the iziGqoza princes, who received little reward for their contribution during the fighting.

The victorious uSuthu were well aware of the role played by Dunn during the battle, and by the presence of the traders cowering nervously on the river-back. In fact, they blamed them for encouraging Prince Mbuyazi’s defiance, and two of them, Walmsley and the leading trader, Rathbone, were explicitly named and shamed in Cetshwayo’s praises – because the political odds were against him, Cetshwayo was likened to a small switch which had managed to stamp out the great conflagration fuelled by Walmseley and Rathbone – ‘The Little Branch of Leaves Which Extinguished the Great Fire Kindled by Matshonga and Rathbone’.

It was not a coincidence, either, that inkosi Mkhosana Biyela had chosen this particular phrase to urge his men on at iSandlwana. In its reference to the supposed role of Europeans at ‘Ndondakusuka it evoked an old grievance against white interference from Natal, an incident which still rankled with many in Zululand, and which in that moment cried out for retribution. The fire had been beaten out before; small wonder the uKhandempemvu rose up to do so again.

And so, that day, they did; the 24th were driven back by their advance, and iSandlwana was over-run. I listened spell-bound at Gilenja told the story, snapping his fingers to conjure up the sound of the bullets as they smacked on the rocks around Mkhosana, and evoking the rush of the uKhandempemvu as they surged past him. Mkhosana had been Gilenja’s grandfather; in the family they had spoken of how he had been dressed that day in all his finery, so much so that they explained his apparent invulnerability in the face of British fire by the assumption that the British had been reluctant to kill him because they thought he was King Cetshwayo himself.

And yet Mkhosana was not invulnerable, and as he turned to join the attack, a bullet passed clean through his head and killed him, this great Zulu hero of the battle falling dead in the moment of his triumph. After the battle Mkhosana’s brother Mthiyaqwa, sought out his body, covering it with Mkhosana’s great war-shield, and returning home to enshrine the story of his death.

And still, as the Zulus say, the young men are gone, but their praises remain – and the story of Gilenja is remembered, and through it two of the bloodiest battles in Zulu history, and the short phrase from a King’s praises, with its reference to the tension which beset the Zulu kingdom in its relationship with the encroaching white world, which linked them together.

I remember last March looking out over that battlefield and thinking how nondescript it was for the horror that took place there.