Bold Decision or Utter Folly; Lord Chelmsford's decision to split his force at iSandlwana

One of the criticisms which is most frequently hurled at Lord Chelmsford - the senior British commander during the invasion of Zululand - is that he brought the catastrophic defeat of iSandlwana upon himself by making the school-boy error of dividing his forces on the eve of battle, without knowing the strength and disposition of his enemy.

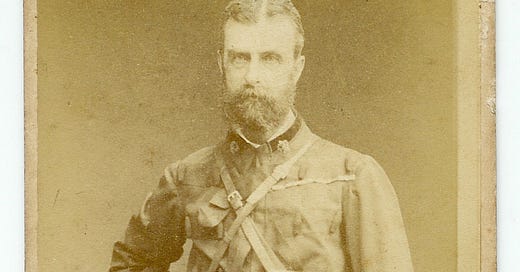

And there is certainly an argument that he should have known better. Chelmsford in 1879 was not an inexperienced soldier, nor indeed a novice commander. He was undoubtedly the product of the Victorian military establishment who had - as was the norm at the time - bought his commission into the Army, and had carefully manoeuvred between fashionable regiments to secure the promotion he desired. He had been present during the Crimean War and the Indian Mutiny - although as John Laband has recently pointed out in his excellent biography of Chelmsford, The Shadow of iSandlwana, he had not seen much actual combat. Nevertheless he had been a staff officer during the British expedition to Abyssinia - Ethiopia - in 1868, a campaign which was perhaps most remarkable because of the efficient staff work which allowed a British column to march from the Red Sea coat into the Ethiopian highlands. More recently, he had succeeded to the command of British troops during the final stages of the 9th Cape Frontier War (1877-78), and had brought to a close that rather messy little war, fought out in a maze of hills and thick bush-covered valleys.

But if the invasion of Zululand was not his first action, how was it he went so disastrously wrong quite so quickly?

They key, perhaps, lies in the fact that the iSandlwana campaign occurred right at the beginning of the war - within a fortnight, in fact, of British troops crossing into Zululand. Lord Chelmsford went into it with his impression of his enemy shaped by his recent experiences on the Cape Frontier. Although he had been advised that the Zulus fought in a very different manner to the Xhosa on the frontier - and indeed, he had himself commissioned an intelligence report on how the Zulu army was formed and functioned - he was misled by that same recent experience. Intellectually he may have known that the Zulu were different to the Xhosa, but he could not quite free himself of the impression that, at the bottom line, they would fight in the same way; that they would not be capable of withstanding disciplined British firepower, and that they would prefer to avoid giving open battle as a result. His strategic thinking was shaped by his understanding that he would need to be the aggressor - that he would have to drive the Zulus into a corner in order to make them fight.

And it was against this assumption that he made the decisions which would undo him - and cost the lives of the defenders of the camp at iSandlwana.

But, in order to understand his decisions, we must look at the context in which they were made - as events unfolded.

Chelmsford had accompanied the British No. 3 (Central) Column which had crossed into Zululand at Rorke’s Drift on 11 January 1879. The following day he had led a demonstration against the followers of the Zulu border inkosi (chief) Sihayo kaXongo whose territory lay across his line of advance; the Zulus were outnumbered but put up a stiff defence among the boulders at the foot of a line of cliffs. They were nevertheless defeated, prompting Chelmsford to remark that they had gallantly resisted - but were no match for British troops. Instead of drawing the conclusion that the Zulu were different to the Xhosa, Chelmsford allowed his existing preconceptions - that, whatever occurred, the Zulus were no match for the British - to be reinforced.

On the 20th, the Centre Column moved forward to establish a new camp at the foot of iSandlwana hill. Even as he arrived there, Chelmsford was aware that the main Zulu army had been assembled at oNdini, and was likely to be directed to attack his column. He was not concerned by this news - he was convinced that he would defeat the Zulu in open battle, and he wanted a swift conclusion to the war. What he was rather more concerned about was the dangers lurking in the terrain ahead of him. The track to oNdini passed across an open plain in front of iSandlwana for about twelve miles before passing through a chain of hills across the head of the Mangeni river. Should the Zulus approach by that route, they would be completely obvious to the garrison at iSandlwana - and for that reason, Chemlsford believed that they would not. Immediately to the left of the camp a ridge known as the iNyoni shut off the view to the north from the foot of iSandlwana, but a line of vedettes placed on the higher ground, on the lip of the escarpment, gave a view across several miles of country. Whilst Chelmsford accepted that a Zulu attack from that direction was possible, he did not think it likely because his Left-Flank Column, under Evelyn Wood, was only thirty miles away on that side.

It was his right flank that bothered Chelmsford. Here a high rocky rampart known as Malakatha mountain gave way to a long ridge called Hlazakazi which framed the track towards oNdini for much of the way to Mangeni; indeed, Hlazakazi’s eastern end dropped off sharply into a deep gorge gouged over millennia by the Mangeni itself. On the other side of Malakatha and Hlazakazi - south of the track to oNdini, and running parallel to it - the country fell away in a rugged series of hills and deep valleys which extended along the banks of the Mzinyathi river - the border - downstream from Rorke’s Drift.

On 20 January - even as his men were unpacking the wagons and setting up their camp at iSandlwana - Chelmsford, his staff and a small escort had ridden to the far end of the Hlazakazi ridge, and looked out across the Mangeni gorge into the wild country beyond. This, Chelmsford decided, was the weak-spot; in the Zulus approached him from oNdini, and were not silly enough to advance down the open plain directly towards iSandlwana, the greatest risk to him was that they might turn to their left - his right - and slip beyond Hlazakazi and Malakatha, using it to screen their movements from iSandlwana, and thereby outflank him, potentially striking across the border and into Natal downstream

The view from above the Mangeni valley, with the eastern end of Hlazakazi on the right. On 20th January Lord Chelmsford and his staff stood on the high point above the sheer cliff face, and looked out over the country in the background here, pondering what might happen if the Zulu army got into those hills downstream of Rorke’s Drift.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Zulu Musings to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.